The first non-American astronaut to set foot on the moon could come from the Land of the Rising Sun.

Only twelve human beings have set foot on the moon so far. All twelve were part of the Apollo missions carried out between 1969 and 1972. All twelve were white American men. With the Artemis Programme, the United States has the stated goal of bringing the first woman and the first non-white person to the moon, but the programme will also end the American monopoly on moonwalks. “America will no longer walk alone on the Moon,” NASA Administrator Bill Nelson tweeted on X. Given all the collaborations that have taken place over the last few decades and are still ongoing, one hoped he was thinking of Italy, or at least Europe. These hopes were misplaced.

ARTEMIS II AND ARTEMIS III

During Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida's visit, Joe Biden announced that two Japanese astronauts will take part in future Artemis missions and that one of them will be the first to set foot on the Moon after the Americans. This is a second disappointment for Europeans, who had already swallowed a bitter pill when Jeremy Hansen joined the three Americans in the Artemis II mission crew: at the 2025 lunar Olympics, the silver medal for “orbiting the Moon” will go to Canada, a country already involved in the International Space Station (ISS) collaboration and the closest ally of the US. These are two disappointing choices for Europe, which has been working for over a decade on the service module of the Orion capsule, the main element of Artemis. However, no choice would have satisfied all the countries of the old continent. Italy's ASI, strengthened by its collaboration in the construction of the ISS and the Lunar Gateway (the lunar space station) and by being the first country to sign the Artemis agreements, was counting on Samantha Cristoforetti, but its cousins across the Alps were also hoping for one of their own: in 2021, Macron even had French astronaut Thomas Pesquet accompany him to a meeting with US Vice President Kamala Harris. Germany and the United Kingdom were also pushing for one of their own, and amid the squabbling, Kishida rejoiced.

A GOLDEN YEAR FOR JAPANESE SPACE EXPLORATION

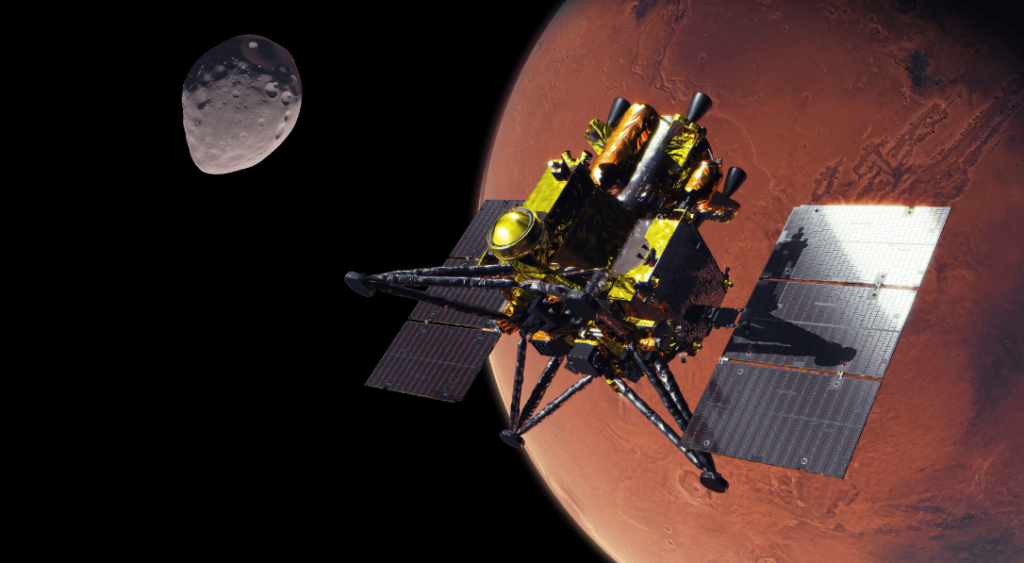

Japan's space programme is enjoying a golden 2024. In February, the Japanese space agency JAXA successfully launched its new heavy-lift rocket H3, which is similar to Falcon 9 in terms of performance. It is not reusable, so it will not revolutionise the launch vehicle market, but it is already more than ESA has achieved with Ariane 6, which has been awaiting its maiden launch for years. Even when it comes to the Moon, JAXA has reason to celebrate: in January, the Slim (Smart Lander for Investigating Moon) lander performed a clumsy but soft landing. The lander bounced on the lunar surface, then settled on its side, with its solar panels pointing not upwards but westwards. JAXA technicians then waited for the Sun to set in the west to try to restart Slim. The lander “woke up”, making Japan the fifth country (five months after India) to have a functioning probe on the lunar surface. Not only that, but Slim enjoyed the lunar sunset so much that the lander also reactivated for the next one in February and the one after that in March. Japan is also doing well in research and interacts a lot with the US. In March, NASA delivered the Megane (Mars-moon Exploration with GAmma ray and NEutrons) instrument to JAXA, a gamma-ray and neutron spectrometer that will be used in the Japanese MMX (Martian Moons eXploration) mission. Scheduled for 2026, the mission aims to investigate the composition and therefore the origin of the Martian moons. Megane, which means “glasses” in Japanese, will study the composition of the moon Phobos and retrieve a sample to bring back to Earth. The Land of the Rising Sun is also making waves in the private sector: last year, the company ispace was responsible for the first private attempt to land a lander on the lunar surface. The M1 mission ended in a crash, but the Japanese company and its subsidiaries in the US and Luxembourg are preparing a new lander and rover for M2, scheduled for the end of this year. In this issue's Space News, we also report on how ispace is preparing to reach the far side of the Moon with M3, using a small constellation of satellites in lunar orbit to ensure communications with the control centre.

A MOON CAMPER

Added to this is the American choice, although there are no significant connections between the Artemis programme and the goals already achieved by Japan. The Japanese Prime Minister gave some examples of these links, citing two major projects: Toyota's Lunar Cruiser and the International Habitation Module. The first is a pressurised lunar rover branded Toyota with an airlock, a standard scientific laboratory capable of providing 30 days of autonomy for astronauts exploring the lunar South Pole; in practice, a sort of lunar camper van. The second is a Lunar Gateway module for which Japan is supplying batteries, life support and environmental control systems. It will be launched with Artemis IV (not before the end of 2028) and will accommodate up to two astronauts for periods of up to 90 days. These are undoubtedly interesting and ambitious projects. Is it thanks to them that Japanese soles were chosen over European ones as the new mould for lunar regolith? Not really. Especially when you consider that most of the module is being built in the Turin factories of the very European Thales Alenia Space and that the rover will not be registered before the Artemis VII mission, by which time Elon Musk may already have reached Mars.

AND EUROPE?

The reason for the US decision is purely diplomatic. The same diplomacy that Kishida displayed in his speech in the US, in which he said and reiterated that Hiroshima is his hometown. There is no other reason to mention the ill-fated Hiroshima in America. In politics, it is not what you say that matters, but what you choose not to say. For example, Biden did not say which mission the first Japanese astronaut will land on the moon with. At the moment, the four astronauts of Artemis III, the mission that will first take two crew members to the moon, are still unknown. They will probably be a woman and a black man from the United States, but nothing is certain yet. Furthermore, the same applies to Europe as to Japan: the agreements stipulate that, in exchange for the work carried out by ESA for Artemis, NASA will guarantee three European astronauts a flight to the Moon, but it has not been established which mission this will be. There is speculation that the first will depart with Artemis IV, but in theory, a citizen of the old continent could reach lunar orbit as early as Artemis III. And it is in the US's interest to hand out these five golden tickets, now that it is the only one that can print them, because very close to its great friend Japan there is another power that aspires to a leading position on the Moon.

CHINA ALSO STAYS CLOSE TO THE MOON

China is successfully pursuing its busy agenda of robotic lunar exploration with the Chang'e missions and is proposing itself as an alternative to the Artemis bloc, driving the construction of a permanent, international robotic lunar base. Russia, Thailand, Pakistan and South Africa have already joined the International Lunar Research Station. Other countries may join, but not the 38 that signed the Artemis agreements, including the “Sinophile” Brazil and the United Arab Emirates, as the agreements prohibit this. Beijing has raised the stakes, declaring that a taikonaut will reach the Moon in 2029, earlier than previously calculated and before the start of construction of the robotic base, but in the centenary year of the birth of the People's Republic of China. The Chinese manned lunar mission, which does not yet have a specific name, is part of a robotic programme and seems to find its raison d'être in challenging the US, along the lines of “we are not to be outdone”. Partly because of the deadline at the end of the decade, the mission is reminiscent of the Apollo programme: the already tested Mengzhou (“Dream Ship”) capsule will take the taikonauts into lunar orbit, where they will rendezvous with the Lanyue (“Lunar Embrace”) lander. This will be landed by two taikonauts, who will also have a small rover with a range of 10 kilometres at their disposal. It is a relatively simple lunar mission, but for some it is unrealistic in terms of timing. However, China has already proven that it can work at a fast pace in the space race, and the space agency already has the engines ready that will power the two rockets to launch the capsule and lander: two Long March 10s, derived from a launcher previously known as Long March 5 and consisting of three stages with a total height of 93 metres. In contrast, the Artemis programme has accustomed us to numerous delays: plans five years ago called for a moon landing this year, but in reality we will not see Artemis III launch before the end of 2026. If, as it seems, Japan will have to wait for Artemis IV to set foot on the Moon, it may already find the words 'Made in China' written on the lunar soil.